Blurb-writing 101: Never Write Your Blurb Before You’ve Read the Book You’re Blurbing. Someone should have told Dan Brown this before he blurbed Mario Livio’s The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World’s Most Astonishing Number (Broadway, 2002). Writes Mr B, “you will never again look at a pyramid, pinecone, or Picasso in the same way.”

Phi, former math majors & readers of The Da Vinci Code (Salman Rushdie: “a book so bad it makes bad books look good”; Stephen Fry: “complete loose stool-water,” “arse-gravy of the worst kind”) will know, is the number you get when you divide a line into the “Golden Ratio,” so that the line as a whole bears the same proportion to the longer division as the longer division does to the shorter – on line ABC, AC is to AB as AB is to BC (or AC:AB :: AB:BC). Dividing the longer segment by the shorter, you get the irrational number 1.6180339887… (to no end).

The Fibonacci Series of numbers, in which each successive number is the sum of the preceeding two (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, etc.) (& which Ron Silliman made use of in Ketjak) has the remarkable property, as you divide each number by its precedent, of more and more closely approximating Phi.

Brown made much of the Golden Ratio in The Da Vinci Code, much of it – that Leonardo plotted his Vitruvian man according to the GR, that the Pyramids are based on the GR, etc. – dead wrong, as Livio demonstrates marvelously clearly* in The Golden Ratio, one of those rare books by a scientist that are actually compulsively readable. Indeed, one of the things that makes this book so entertaining is the amount of time it spends debunking various applications of Golden Numerology – all of which Brown seems (from my rather foggy memory of Da Vinci Code) to have swallowed whole. In other words, while there are applications of the Fibonacci series to the arrangement of pinecones, anything relating the Pyramids or Picasso to the golden ratio is just so much hooey – as Brown would have realized if he’d read Livio before praising him.

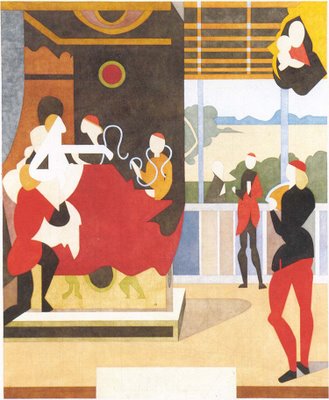

Reading Livio sent me back to one of my favorite artists, Tom Phillips, whose After Raphael [above] was imprinted on me early by being reproduced on the cover of Brian Eno’s Another Green World. (Eno was a student of Phillips’s at art school.) Unfortunately, like Brown Phillips seems to have swallowed all the balleyhoo about the omnipresence of the golden ratio:

Even the most ill-proportioned visitor to Greece will have it in his bones before he leaves: temple and statue, pillar and pavement, speak the same harmony. Its rediscovery as one of the lost truths of antiquity lay at the heart of the Renaissance. As in the paradox of the poet freed by rhyme, the artist can be liberated by a system of great rigidity. The airy, tender and spacious compositions of Piero reveal, under geometrical analysis, that not an eye or elbow has its place but at the conjunction of lines generated by the overall proportions of the picture.I’m all for being “liberated by a system of great rigidity.” And I suppose the golden section is as good as any other system. But why does everyone have to pretent that the damn thing goes all the way back to the Egyptians, when a little bit of spadework will show otherwise? “Blessed rage for order,” indeed.

I’m just glad LZ never got ahold of the golden ratio; heaven knows he did enough damage with a smattering of second-hand calculus and a fistful of Pythagorean number lore.

*Though not with direct reference to Brown’s book, which didn’t come out until the following year. I suspect Livio’s publisher, which also did the “illustrated” Da Vinci Code, solicited Brown to blurb the paperback of The Golden Ratio.

No comments:

Post a Comment