USAirways seems to have lost my suitcase, which contained (along with a lot of sentimentally-valuable clothes) copies of Josh Corey’s Compos(t)ition Marble, Michael Heller’s A Look at the Door with the Hinges Off, Lawrence Upton’s Wire Sculptures, and Peter Riley’s Passing Measures. That’s what I get for trying to save weight in the shoulder bag by packing the already-read books in the checked luggage.

***

Somebody seems to have been giving Bob Archambeau trouble about his Adorno posts, to which Bob responds feistily. My experience is that hardcore Adornauts can indeed be a bit on the Spanish Inquisitorial side (which is why I read a lot of Adorno but don’t write a lot about him, until I’m double-dog sure I’m right) – probably a side effect of having invested so much psychic energy into making out what the Bald & Oracular One’s saying.

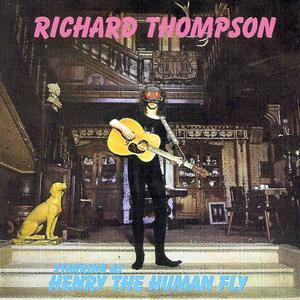

But I think Bob’s a trifle off-key in his responses. First, while I see the value of paraphrase, I think I’d be happier comparing it to translation (as Bob does) than to performance, eg of a musical score. Paraphrase is to text not as Michael Tilson Thomas’s conducting of (say) Mahler is to Mahler’s score of the 8th Symphony, but as a piano redaction of the 8th Symphony is to the original score; or as a Muzak adaptation of an Iggy Pop tune is to the original recording. Yes, you can learn something from the redaction & the Muzak, but it’s not the original, no not at all. Richard Thompson’s cover of Britney Spears’s “Oops I Did It Again” teaches us that it’s a pretty damned good pop song – but we could have learned that as readily by reading the sheet music & thereby bypassing the aural and visual distraction of the blonde one.

So it’s a bit unfair to slam Adorno for preferring the sheet music, considering he’s in pretty good company – Beethoven (perforce), George Antheil, Paul Zukofsky – a list of fellows not at all averse to performance, but finding that they grasp the immanent structure of the music much better without the distraction of actual musicians flubbing notes and concert-goers coughing etc.

I don’t remember a passage where Adorno asserts the primacy of German as “a special language, with unique affinities for philosophy” (tho Bob might remind me of one). He did claim the necessity of thinking and moving in a German linguistic environment as one of his reasons for returning to the BRD after the war. And I suspect that he did believe in some ways German was the language in which to do the sort of philosophy he did. An argument can be made that just as English is the language of pragmatism, & French the language of deconstruction, German is the language of Kantian and post-Kantian idealism – that the concepts and key ideas of idealist philosophy (the Kant – Hegel – Marx tradition in which Adorno moves) are absolutely embedded in the German language, & that when we try to translate them to another tongue – with whatever good intentions – they undergo an inevitable transformation, even violence. German is, in that sense, the only language in which to do (the particular) philosophy (that follows from Kant & Hegel). In one sense, it’s no more debateable than arguing that it’s easier to write a canzone in Italian than English, because the former language has lots & lots more rhyming words.

Heidegger, on the other hand, asserts something rather different & rather creepier: that German (along with classical Greek, which he saw as conceptually cognate with German) has some obscure and fundamental connection to the roots of Being (Seyn, as he archaically spelled it). That’s a far more foundationalist argument about language & philosophy.

Just for fun, Adorno on Heidegger, from “The Essay as Form”:

Whenever philosophy imagines that by borrowing from literature it can abolish objectified thought and its history – what is commonly termed the antithesis of subject and object – and even hopes that Being itself will speak, in a poésie concocted of Parmenides and Jungnickel, it starts to turn into a washed-out cultural babble.

***

I have no New Year's resolutions (tho I'll be trying to live up to my blue china); a happy one to you all.