The four or five people out there who read my Anarchy know that I have a bit of an obsession with 17th-century British history, in particular in the intersection of orthodox and heterodox Christian beliefs and radical political movements. I am also happy to admit that I love historical costume-dramas, from Ken Hughes's broad-brush potboiler Cromwell (1970), to James Clavell's intriguing but deeply flawed Thirty Years' War flick The Last Valley (1971) – and not excepting Stanley Kubrick's near-static take on Thackeray's Barry Lyndon (1975). They must all now bow down in my personal pantheon to Kevin Brownlow's low-budget 1975 masterpiece Winstanley.

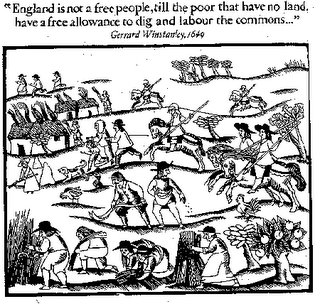

Gerrard Winstanley (1609-1676) was a radical pamphleteer during the Civil War period (along with about 50,000 others, it seems), a man with an argument: that the Lord had created the land as "a common treasury for all," that social subordination was contrary to God's intention for humanity: "in the beginning of time God made the earth. Not one word was spoken at the beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another, but selfish imaginations did set up one man to teach and rule over another." In 1649, the year of King Charles's beheading and the final triumph of Parliament's revolution, Winstanley led a small group of followers to "common" land on St. George's Hill, Surrey, where they established a small egalitarian agricultural colony that they hoped would be self-sustaining, beyond the necessity for buying, selling, and subordinating themselves to market logic and market hierarchies. In short, a proto-hippie socialist commune. It didn't last, of course: the "Diggers" (or "true Levellers"), as Winstanley's group was known, were driven off of the "commons" – lands technically reserved for cattle grazing, and off-limits for agriculture or wood-cutting – by forces of the local landowners.

By the late 1960s, when the very young Kevin Brownlow started work on Winstanley, his second film, the radical elements of the English Revolution were very much in the air among the British Left. (And here's a difference between the British and American Leftist traditions that intrigues me: unlike the Americans, the British can lay claim to a very venerable radical tradition indeed, one that's deeply intertwined with the tradition of religious dissidence – one that by some accounts goes as far back as the indigenous resistance to the Norman Conquest.) In 1972 the great Marxist historian Christopher Hill published his The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution, a volume that works very explicitly to establish a 17th-century intellectual pedigree for the student movement and other contemporary Leftist causes. (For very late Hill on Winstanley, see here.)

Brownlow's Winstanley is the diametric opposite of Hughes's Cromwell. The latter film was packed with color and expensive costuming and jammed with big stars – Alec Guinness as King Charles, Richard Harris as Cromwell, a very young Timothy Dalton as Prince Rupert. Hughes shot his film in black and white; the only real "actor" in Winstanley was Jerome Willis as General Fairfax, all of the other roles being taken by amateurs (for the most part an inspired stroke – for the film's band of "Ranters," Brownlow enlisted a party of contemporary hippie commune-dwellers who considered themselves the new Diggers); and while Brownlow's overall budget was something short of what it cost to film the opening credits for the latest James Bond feature, he went to absurd lengths to ensure the authenticity of his costumes, props, and scenes (in this rather like Kubrick in Barry Lyndon).

One way of conceiving Winstanley is to think of Barry Lydon's visual beauty and deliberate pace, distended (stripped of sumptuous soundtrack music, the long shots even more protracted) or Beckettesquely minimalized (no color, no more beautiful people – Brownlow's actors are remarkably real – dirty, shabby, unshaven, bad-toothed), and animated thruout by the stately rhythms of 17th-century English prose & the luminous power of Winstanley's ideas. At times – really very magical moments – one forgets that one is watching "fiction," the power of Brownlow's cinematography is so compelling, and one is convinced that one is watching an anthropological documentary filmed, by some species of necromancy, on a hill in Surrey in 1649. Unforgettable.

2 comments:

Barry Lydon, now there's a Freudian slit...

Are you going to reflect here on what sense there is to be made of a post-Zukovskyan tradition with an ambiguous pull towards closed forms?

"Dirty, shabby, unshaven, bad-toothed": yup, sounds like "Barry Rotten" to me!

Nice piece, Mark!

EMS

Post a Comment