Well, it's been a bit like hunkering down in some hardened-concrete Führer-bunker, pulling on one's gasmask & flak jacket, & then realizing that the much-anticipated attack was only a couple of kids throwing snowballs – and only a couple of snowballs.

Ernesto was supposed to come ashore between midnight & 2AM as a tropical storm – possibly even a weak hurricane. I spent much of today on preparations: putting up about half of our storm shutters (in the process straining an already strained wrist – too many "swing me again, Daddy"s – to where I couldn't use it without an ace bandage) (and oh yeah, almost breaking my ankle in the inevitable drop from the second floor roof, which is too long a story to go into), moving everything that could possibly move that was outside inside, waiting in line for gas, finding space for all those extra gallons of water, etc.

And now the radar shows that the storm has arrived early & is probably about halfway over, without giving us anything more than an average summer afternoon thundershower packs.

This is of course karma: if I hadn't put up the shutters, we'd be sweeping rain out of the closets.

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Monday, August 28, 2006

I spoke too soon, in re/ Tropical Storm (by Wednesday Hurricane?) Ernesto ("Che"). Yes I'm worried, but mostly dreading putting up those bloody shutters. Details here. (For wry & nervous hurricane watching, you can't beat my homey Su.)

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Announcing: The Scroggins Consumer Guide

The weekend nears its end, & I’m a trifle less worried about hurricane/tropical storm Ernesto (whom I fondly think of as “Che”) than I was a few days ago. Those of you who don’t live in hurricane-prone states don’t really know what a nail-biting experience the Fall months can be here is South Florida, a Place Where God Didn’t Mean Human Beings To Live But Capital Came In Paved Everything & Put Up Ugly Buildings. The National Hurricane Center’s website is probably the most visited bookmark on my browser these days.

However, for those who may be getting a slightly inaccurate picture of my surroundings from the somewhat romanticized imaginings of Bob Archambeau, a brief primer:

1) The “swamps” have mostly been paved over & filled in; the climate, of course, remains eminently swampy. Over 90 this weekend.

2) While I grew up amid kudzu and Southern Baptists, there is very little kudzu in South Florida. That’s part of the real South, & SoFla, as everybody knows, is actually two little cultural principalities all their own which have nothing to do with the historical South. The lower part could be called “Havana away from Havana”; the upper part (in which I live), could be called “New Jersey/Long Island: Southern Annex.” (Contrary to popular belief, real New Yorker Cityites rarely retire to Florida, but prefer to die where they can still feel the asphalt between their toes and the grit under their eyelids.)

3) Yurt? What yurt?? I suspect this has something to do with Bob’s sneakily malignant characterization of me as a hulking, hirsute Bigfoot or Sasquatch, perhaps with a touch of Yeti thrown in for good measure. For the record: I stand about 6’ & wear shoe size 11 – big, but nothing special; I do wear a beard (to keep from looking like Karl Rove), but I trimmed down the Osama bin Laden job some years ago, as I kept getting asked directions to the nearest Lubuvicher Temple.

***

Bob does a nice job of exfoliating what I was thinking about the blandness of poetry reviews, to which I can only add a few thoughts. First, the lovely “baboon feces” analogy: we hurl feces at the other baboon tribes all the time, but usually on what we think of as principled grounds: ie, the other tribes’ aesthetic is somehow fundamentally flawed, they don’t recognize us as real players, etc. For my money, it’s a silly game & a waste of energy (not that I haven’t done it): write about the poets you care about, or write about poets whose ambitions you respect or share, even (or especially) if they don’t manage to realize those ambitions.

Then there’s the “consumer advice” that Bob notes & dismisses in his first post. I’m not sure that consumer advice shouldn’t be reinstated as a reviewerly ideal. Those of you who read Creem back in the day, remember Christgau’s “Consumer Guide”? (Yes, yes, all you hipsters out there read it in the Voice, but where I grew up the only "Voice" periodicals available were run by evagelical sects...) Now that’s a column that I really miss: single paragraph reviews of new albums – brief, pithy descriptions and an A thru E- letter grade. The “Guide” worked for a number of reasons:

***

Noting that I'm surfing thru the Scriptures, & perhaps fearing I might fall into theism, Jessica passes on the URL for Dwindling in Unbelief. Hmmm. Kind of fun – debating the scriptural literalists on their own ground – but in the end it strikes me as rather pointless, rather like arguing with one of those "Shakespeare authorship" cranks. There's so much wonderful biblical scholarship out there – textual, historical, theological – that life is too short to spend it arguing with those who'd take the book their version of "literally." My own experience of reading scripture has been that for all its barbarity, incoherency, self-contradiction, repetition, long stretches of tedium, etc., the Bible becomes a stranger & more wonderful book every time thru.

Of course, we can't forget that those who read the thing literally (who're counting the days till the rapture, & who can't wait for WWIII to start up so the 2nd Coming'll be on time) are the ones with access to the White House these days...

***

And dig that Katherine Harris, bleating to the believers as her poll numbers spiral perdition-ward. (Thanks, Incertus.)

However, for those who may be getting a slightly inaccurate picture of my surroundings from the somewhat romanticized imaginings of Bob Archambeau, a brief primer:

1) The “swamps” have mostly been paved over & filled in; the climate, of course, remains eminently swampy. Over 90 this weekend.

2) While I grew up amid kudzu and Southern Baptists, there is very little kudzu in South Florida. That’s part of the real South, & SoFla, as everybody knows, is actually two little cultural principalities all their own which have nothing to do with the historical South. The lower part could be called “Havana away from Havana”; the upper part (in which I live), could be called “New Jersey/Long Island: Southern Annex.” (Contrary to popular belief, real New Yorker Cityites rarely retire to Florida, but prefer to die where they can still feel the asphalt between their toes and the grit under their eyelids.)

3) Yurt? What yurt?? I suspect this has something to do with Bob’s sneakily malignant characterization of me as a hulking, hirsute Bigfoot or Sasquatch, perhaps with a touch of Yeti thrown in for good measure. For the record: I stand about 6’ & wear shoe size 11 – big, but nothing special; I do wear a beard (to keep from looking like Karl Rove), but I trimmed down the Osama bin Laden job some years ago, as I kept getting asked directions to the nearest Lubuvicher Temple.

***

Bob does a nice job of exfoliating what I was thinking about the blandness of poetry reviews, to which I can only add a few thoughts. First, the lovely “baboon feces” analogy: we hurl feces at the other baboon tribes all the time, but usually on what we think of as principled grounds: ie, the other tribes’ aesthetic is somehow fundamentally flawed, they don’t recognize us as real players, etc. For my money, it’s a silly game & a waste of energy (not that I haven’t done it): write about the poets you care about, or write about poets whose ambitions you respect or share, even (or especially) if they don’t manage to realize those ambitions.

Then there’s the “consumer advice” that Bob notes & dismisses in his first post. I’m not sure that consumer advice shouldn’t be reinstated as a reviewerly ideal. Those of you who read Creem back in the day, remember Christgau’s “Consumer Guide”? (Yes, yes, all you hipsters out there read it in the Voice, but where I grew up the only "Voice" periodicals available were run by evagelical sects...) Now that’s a column that I really miss: single paragraph reviews of new albums – brief, pithy descriptions and an A thru E- letter grade. The “Guide” worked for a number of reasons:

•It was by a single person, so that whether you thought Christgau was brilliant or entirely misguided, you could calibrate your own tastes in relation to his & figure out what was worth buying & what was worth a miss.So let me make a formal announcement: I can’t really get around the fact that I’ve got an investment as a poet myself, but I’m willing to take on a pseudonym & become a full-time poetry reviewer – no holds barred, any school or tendency welcome, up to 30 books a month covered in “consumer guide” format – for any venue that wants to replace my day job’s salary dollar for dollar. (Tenure and benefits would be nice, as well.)

•Christgau didn’t mind stepping on toes, because he didn’t have his own record all ready on ProTools & was worried about some guy at A&M Records blacklisting him; this was what he did, & it was all he did (& even the biggest slacker of a poet with a day job or an academic gig is pretty hard pressed to turn out 2 or 3 brief reviews a month, much less cover a dozen books every few weeks).

•Both of which were made possible by the fact that Christgau wasn’t just doing it for the free LPs – he was getting paid real money.

***

Noting that I'm surfing thru the Scriptures, & perhaps fearing I might fall into theism, Jessica passes on the URL for Dwindling in Unbelief. Hmmm. Kind of fun – debating the scriptural literalists on their own ground – but in the end it strikes me as rather pointless, rather like arguing with one of those "Shakespeare authorship" cranks. There's so much wonderful biblical scholarship out there – textual, historical, theological – that life is too short to spend it arguing with those who'd take the book their version of "literally." My own experience of reading scripture has been that for all its barbarity, incoherency, self-contradiction, repetition, long stretches of tedium, etc., the Bible becomes a stranger & more wonderful book every time thru.

Of course, we can't forget that those who read the thing literally (who're counting the days till the rapture, & who can't wait for WWIII to start up so the 2nd Coming'll be on time) are the ones with access to the White House these days...

***

And dig that Katherine Harris, bleating to the believers as her poll numbers spiral perdition-ward. (Thanks, Incertus.)

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Ad Interim

Recovering from the first week of classes here – myself, Pippa, & Daphne (for whom this is the first time around, & she's taking to it swimmingly, thank you v. much); but not J., who has a semester's research release so she can lounge about eating bonbons (well, not really). Pippa (aet. 4 1/2) came home Tuesday and announced, "I can read!" Which, it turned out, she could: I tested her on a brand new "phonics" letter game we hadn't opened, & she buzzed right thru 35 of the 36 3-letter words therein (the only one she had trouble with was "boy," one of those damned tricky English diphthongs which could conceivably be spelled any number of ways – boy, boye, boi, even beu).

One's always pleased with one's own kids, often with the slimmest of reasons. I admire the forthrightness of one of my students some years back: A vice president at one of those ubiquitous "security" companies (right now I'm told they're guarding ex-Soviet missile siloes & industrial sites in Mexico, patrolling the Sinai, & operating all the prisons in Scotland), he had just moved to SoFla & was deciding whether to send his kids to private or public schools. He was told that while his local public school was a problematic bet, the "gifted" program was excellent, & having something of a social conscience (at least enough to theoretically want to support the public school system), he inquired as to how one gets one's kids into the "gifted" program. "After all," he told me, "my kids aren't 'gifted'; they're great kids, & I love them very much, but they're not really all that brilliant." It doesn't matter, he was told – if a family was able to pony up to have the child tested by a psychiatrist (& this was something the state would not pay for), then that was usually considered prima facie evidence that the kid was gifted, whatever the test results said. Realizing that the State of Florida had thereby built class distinctions right into the public school system, my student decided to cut out the middleperson & directly enroll them in private school.

***

Bob Archambeau spends some time explaining why he savaged Gabriel Fitzmaurice's latest collection. Truly dire stuff (the book reviewed, not the review or apology thereupon), but I wonder if Bob ain't skirting the more proximate reason why there aren't more bad reviews of new books of poetry in the circles in which we travel: ie, because it's after all a pretty small world, the world of contemporary poetry that one cares about or theoretically ought to care about, & one's always chary of treading the toes of someone who might be willing to publish or review one's own work the next time around. I'm all for those careful, descriptive reviews of projects that one's largely sympathetic with; I'd like to see more critical, even cutting evaluations of worthwhile projects that one wishes succeeded but don't.

***

Looking forward to the contents of John Latta's attention span – noting how our zones of weariness seem strangely to have overlapped at approximately the same time – & wondering if any of the same books have swum into our ken over the last year.

One's always pleased with one's own kids, often with the slimmest of reasons. I admire the forthrightness of one of my students some years back: A vice president at one of those ubiquitous "security" companies (right now I'm told they're guarding ex-Soviet missile siloes & industrial sites in Mexico, patrolling the Sinai, & operating all the prisons in Scotland), he had just moved to SoFla & was deciding whether to send his kids to private or public schools. He was told that while his local public school was a problematic bet, the "gifted" program was excellent, & having something of a social conscience (at least enough to theoretically want to support the public school system), he inquired as to how one gets one's kids into the "gifted" program. "After all," he told me, "my kids aren't 'gifted'; they're great kids, & I love them very much, but they're not really all that brilliant." It doesn't matter, he was told – if a family was able to pony up to have the child tested by a psychiatrist (& this was something the state would not pay for), then that was usually considered prima facie evidence that the kid was gifted, whatever the test results said. Realizing that the State of Florida had thereby built class distinctions right into the public school system, my student decided to cut out the middleperson & directly enroll them in private school.

***

Bob Archambeau spends some time explaining why he savaged Gabriel Fitzmaurice's latest collection. Truly dire stuff (the book reviewed, not the review or apology thereupon), but I wonder if Bob ain't skirting the more proximate reason why there aren't more bad reviews of new books of poetry in the circles in which we travel: ie, because it's after all a pretty small world, the world of contemporary poetry that one cares about or theoretically ought to care about, & one's always chary of treading the toes of someone who might be willing to publish or review one's own work the next time around. I'm all for those careful, descriptive reviews of projects that one's largely sympathetic with; I'd like to see more critical, even cutting evaluations of worthwhile projects that one wishes succeeded but don't.

***

Looking forward to the contents of John Latta's attention span – noting how our zones of weariness seem strangely to have overlapped at approximately the same time – & wondering if any of the same books have swum into our ken over the last year.

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

Boredom Aesthetics

Good transatlantic comments regarding scripture. Alex Davis remarks that his year of biblical studies at Sheffield did far less to alter his appreciation of the Old Testament than did Monty Python and the Holy Grail; he quotes one of my favorite bits:

Tedium can be funny, as the Pythons demonstrate repeatedly (and cf. Borat singing the endless Khazak national anthem to a stadium of bemused then uncomfortable minor-league baseball fans). But in eccelesiastical settings – as in my childhood, when each church service began with a line of young boys reading, seriatim, five or six verses of scripture apiece (and I assume that this goes double or treble in temple when they’re ploughing thru the census data in Numbers) – tedium is simply tedious.

I think Michael Peverett is right to see tedium as having become, with the modernists, a fundamental component of certain literary texts, an aesthetic element in its own right:

One can I think set aside the question of intentional versus unintentional tedium. “Eumaeus” is clearly intended to be tedious, while Pound felt that the Chinese history Cantos were really great stuff, as dreadfully dull as most of his contemporary readers find them. More interesting is to look at tedium from the side of the bored reader.

One clear taxonomical distinction can be drawn on the basis of understanding. That is, there are passages that we find boring, even as we understand precisely what they mean: "Eumaeus," most of Leviticus, etc. And then there is a sort of boredom that accompanies the reading of a text that one simply can't understand. I don't want to sound like one of my undergrads here – "I couldn't understand Paradise Lost I, so it was sooo boring" – but there's a kernel of truth there: linear meaning is one of the most prominent pegs – historically, the preëminent peg – upon which to hang a reader's attention, & solicit her or his potential enjoyment. (Marianne Moore: "We do not admire what we do not understand.")

The various modernist poetries – and here I'm thinking much more widely than Anglo-American "high" modernism; think Dada, Zaum, Merz, usw. – often worked to set aside linear meaning in the vulgar sense (ie, a coherent discourse that could be attributed to a single lyric voice, or that could be traced out & however reductively paraphrased [both Ben Jonson & Yvor Winters felt poetry should be paraphraseable]). In the wake of these modernisms, we have a variety of poetries that resist meaning in various ways.

Now it's not that the resistance to meaning is in itself boring or productive of readerly tedium: but one might argue that meaning-resistant poetry tends unintentionally to solicit readerly boredom in ways analogous to those in which KJV repetition and Eumaean banality solicit readerly boredom. When I read an obdurately meaning-resistant text, my linearly-trained reading skills have been deprived of one of their primary objects of pleasure (that would be the pleasure of sheer decoding, of learning things); in return, that text must provide me some other sources of pleasure – striking juxtaposition, shiny complexity, a challenging polysemic surface, etc.

And while those pleasures are all very real, when I confront a 150- or 200-page poem composed of nothing but juxtaposition, I'm likely to fall into the boredom produced by repetition ("Then shalt thou count to three, no more, no less. Three shall be the number thou shalt count, and the number of the counting shall be three...") That's often my own failure, my own shortness of attention. Sometimes, however, it's because a poetry of radical disjunction simply can't hold one's attention in the long run unless it has some other qualities of interest, & too many poets (modern & contemporary) have found disjunction to be an end in itself.

Back in the day there was a discussion on the Poetics List about the aesthetics of boredom, and a couple of folks (I won't name names because I don't remember who it was) were arguing for an aesthetics of boredom – that is, of dullness as a kind of textural quality of the poem. That, like the aesthetic of the Chrysler K car and the fact that some people actually buy Britney Spears records, I don't really understand – sort of like arguing the merits of Kenny G over Ornette – or rather, arguing that time spent listening carefully to Kenny G is somehow equal to time spent listening carefully to Charlie Parker. I spend plenty of time reading poetry – not enough – but I begrudge every minute where the poem before me isn't engaging me to my utmost.

King Arthur: Consult the Book of Armaments.Now why’s that funny? Obviously there’s the snazzy Pythonesque cross-cutting of sacred and contemporary diction – “And the Lord did grin,” “who, being naughty in my sight, shall snuff it.” Those contemporary idioms act as punctuation to the more uncomfortable humor of the repetitive, incantatory verbiage which pretty evilly apes the language in which the AV renders ritual instruction: “Then shalt thou count to three, no more, no less. Three shall be the number thou shalt count, and the number of the counting shall be three. Four shalt thou not count, neither count thou two, excepting that thou then proceed to three…”

Brother Maynard: Armaments, chapter two, verses nine through twenty-one.

Cleric: [reading] And Saint Attila raised the hand grenade up on high, saying, "O Lord, bless this thy hand grenade, that with it thou mayst blow thine enemies to tiny bits, in thy mercy." And the Lord did grin. And the people did feast upon the lambs and sloths, and carp and anchovies, and orangutans and breakfast cereals, and fruit-bats and large chu...

Brother Maynard: Skip a bit, Brother...

Cleric: And the Lord spake, saying, "First shalt thou take out the Holy Pin. Then shalt thou count to three, no more, no less. Three shall be the number thou shalt count, and the number of the counting shall be three. Four shalt thou not count, neither count thou two, excepting that thou then proceed to three. Five is right out. Once the number three, being the third number, be reached, then lobbest thou thy Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch towards thy foe, who, being naughty in my sight, shall snuff it.

Brother Maynard: Amen.

Tedium can be funny, as the Pythons demonstrate repeatedly (and cf. Borat singing the endless Khazak national anthem to a stadium of bemused then uncomfortable minor-league baseball fans). But in eccelesiastical settings – as in my childhood, when each church service began with a line of young boys reading, seriatim, five or six verses of scripture apiece (and I assume that this goes double or treble in temple when they’re ploughing thru the census data in Numbers) – tedium is simply tedious.

I think Michael Peverett is right to see tedium as having become, with the modernists, a fundamental component of certain literary texts, an aesthetic element in its own right:

Somewhere along the line the bizarre aesthetic appeal of long screeds of boredom got into modernism - someone got tired of books that were too straightforwardly digestible. I think it begins with Portrait of the Artist - that chapter where the hellfire sermon just goes on and on, (judged by the standards of what earlier novelists and readers would have considered tolerable - they'd have extracted about a page, merely enough to make the narrative point). Must have been a reaction gainst conventional ideas of what was considered proportional (I guess that behind Joyce lay Flaubert, Bouvard and the Tentation... authors intoxicated with pursuing parodic lines far beyond the limits of anecdote - and then there was Ulysses...Michael’s genealogy of tedium, then, involves a Blakean pursuit of parodic excess – the obvious example being the “Nausicaa” and “Eumaeus” chapters of Ulysses, each of which takes a parodic joke way beyond the limits of what any earlier writer would have dreamed. And then there's Samuel Beckett's early novels...

One can I think set aside the question of intentional versus unintentional tedium. “Eumaeus” is clearly intended to be tedious, while Pound felt that the Chinese history Cantos were really great stuff, as dreadfully dull as most of his contemporary readers find them. More interesting is to look at tedium from the side of the bored reader.

One clear taxonomical distinction can be drawn on the basis of understanding. That is, there are passages that we find boring, even as we understand precisely what they mean: "Eumaeus," most of Leviticus, etc. And then there is a sort of boredom that accompanies the reading of a text that one simply can't understand. I don't want to sound like one of my undergrads here – "I couldn't understand Paradise Lost I, so it was sooo boring" – but there's a kernel of truth there: linear meaning is one of the most prominent pegs – historically, the preëminent peg – upon which to hang a reader's attention, & solicit her or his potential enjoyment. (Marianne Moore: "We do not admire what we do not understand.")

The various modernist poetries – and here I'm thinking much more widely than Anglo-American "high" modernism; think Dada, Zaum, Merz, usw. – often worked to set aside linear meaning in the vulgar sense (ie, a coherent discourse that could be attributed to a single lyric voice, or that could be traced out & however reductively paraphrased [both Ben Jonson & Yvor Winters felt poetry should be paraphraseable]). In the wake of these modernisms, we have a variety of poetries that resist meaning in various ways.

Now it's not that the resistance to meaning is in itself boring or productive of readerly tedium: but one might argue that meaning-resistant poetry tends unintentionally to solicit readerly boredom in ways analogous to those in which KJV repetition and Eumaean banality solicit readerly boredom. When I read an obdurately meaning-resistant text, my linearly-trained reading skills have been deprived of one of their primary objects of pleasure (that would be the pleasure of sheer decoding, of learning things); in return, that text must provide me some other sources of pleasure – striking juxtaposition, shiny complexity, a challenging polysemic surface, etc.

And while those pleasures are all very real, when I confront a 150- or 200-page poem composed of nothing but juxtaposition, I'm likely to fall into the boredom produced by repetition ("Then shalt thou count to three, no more, no less. Three shall be the number thou shalt count, and the number of the counting shall be three...") That's often my own failure, my own shortness of attention. Sometimes, however, it's because a poetry of radical disjunction simply can't hold one's attention in the long run unless it has some other qualities of interest, & too many poets (modern & contemporary) have found disjunction to be an end in itself.

Back in the day there was a discussion on the Poetics List about the aesthetics of boredom, and a couple of folks (I won't name names because I don't remember who it was) were arguing for an aesthetics of boredom – that is, of dullness as a kind of textural quality of the poem. That, like the aesthetic of the Chrysler K car and the fact that some people actually buy Britney Spears records, I don't really understand – sort of like arguing the merits of Kenny G over Ornette – or rather, arguing that time spent listening carefully to Kenny G is somehow equal to time spent listening carefully to Charlie Parker. I spend plenty of time reading poetry – not enough – but I begrudge every minute where the poem before me isn't engaging me to my utmost.

Sunday, August 20, 2006

Restoration Nihilism

Samuel Johnson, on John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester (1647-1680, lately portrayed by Johnny Depp in The Libertine): “in a course of drunken gaiety, and gross sensuality, with intervals of study perhaps yet more criminal, with an avowed contempt of all decency and order, a total disregard to every moral, and a resolute denial of every religious obligation, he lived worthless and useless, and blazed out his youth and health in lavish voluptuousness; till, at the age of one and thirty, he had exhaustered the fund of life, and reduced himself to a state of weakness and decay.” His best poem, according to Johnson, is “Upon Nothing” (1678):

Samuel Johnson, on John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester (1647-1680, lately portrayed by Johnny Depp in The Libertine): “in a course of drunken gaiety, and gross sensuality, with intervals of study perhaps yet more criminal, with an avowed contempt of all decency and order, a total disregard to every moral, and a resolute denial of every religious obligation, he lived worthless and useless, and blazed out his youth and health in lavish voluptuousness; till, at the age of one and thirty, he had exhaustered the fund of life, and reduced himself to a state of weakness and decay.” His best poem, according to Johnson, is “Upon Nothing” (1678):Nothing, thou elder brother even to Shade,

Thou hadst a being ere the world was made,

And (well fixed) art alone of ending not afraid.

Ere time and place were, Time and Place were not,

When primitive Nothing, Something straight begot;

Then all proceeded from the great united what.

Something, the general attribute of all,

Severed from thee, its sole original,

Into thy boundless self must undistinguished fall.

Yet Something did thy mighty power command

And from thy fruitful Emptiness’s hand

Snatched men, beasts, birds, fire water, air, and land.

Matter, the wicked’st offspring of thy race,

By Form assisted, flew from thy embrace,

And rebel Light obscured they reverend dusky face.

With Form and Matter, Time and Place did join;

Body, thy foe, with them did leagues combine

To spoil thy peaceful reign and ruin all thy line.

But turncoat Time assists the foe in vain

And bribed by thee destroys their short-lived reign

And to thy hungry womb drives back the slaves again.

Thy mysteries are hid from laic eyes,

And the divine alone by warrant pries

Into thy bosom, where the truth in private lies.

Yet this of thee the wise may truly say,

Thou from the virtuous nothing tak’st away,

And to be part of thee the wicked wisely pray.

Great Negative, how vainly would the wise

Inquire, define, distinguish, teach, devise

Didst thou not stand to point their dull philosophies.

Is or Is Not, the two great ends of Fate,

And True and False, the subject of debate

That perfects or destroys the vast designs of state,

When they have racked the politician’s breast,

Within they bosom must securely rest

And when reduced to thee are least unsafe and best.

But Nothing, why does Something still permit

That sacred monarchs should at council sit

With persons thought, at best, for nothing fit,

While weighty Something modestly abstains

From princes’ affairs and from statesmen’s brains;

And nothing there like stately Nothing reigns.

Nothing, that dwell with fools in grave disguise,

For whom they reverend forms and shapes devise,

Lawn sleeves, and furs, and gowns, when they like thee look wise.

French truth, Dutch prowess, British policy,

Hibernian learning, Scotch civility,

Spaniards’ dispatch, Danes’ wit are mainly seen in thee.

The great man’s gratitude to his best friend,

Kings’ promises, whores’ vows, to thee they bend,

Flow swiftly to thee and in thee ever end.

Friday, August 18, 2006

Scriptural Tedium

I’ve been buzzing quite happily thru Genesis & Exodus over the past few days, reminding myself just what an absorbing reading experience the Bible can be. Now there are friends of mine – well-read, cultured folks, with finely developed literary sensibilities – who are under the impression that all of the Bible is insufferably tedious. Well that’s certainly not the case – but after about 70 consecutive chapters of mostly rivetting stuff, I’ve run (in the 2nd half of Exodus) into one of those patches that only a masochist could love: the deity’s endlessly detailed instructions to Moses on how to construct the Tabernacle, the Ark of the Covenant (remember Indiana Jones?), & various other doodads the Children of Israel will need in their upcoming travels.

It got me to thinking about scriptural tedium, about how there’s exciting bits and dull bits in the Bible, & that got me thinking (as is my wont) about taxonomies. It seems to me the dull bits of the Bible fall into a limited number of categories. First, there are things that are dull in and of themselves:

Then there are things which are inherently rather interesting, often quite fascinating – but only in moderation; in quantity they become a blur of repetition:

It got me to thinking about scriptural tedium, about how there’s exciting bits and dull bits in the Bible, & that got me thinking (as is my wont) about taxonomies. It seems to me the dull bits of the Bible fall into a limited number of categories. First, there are things that are dull in and of themselves:

•Genealogies, those endless lists of ancestors most of whose names sound alien & indistinguishable to the English-speaking reader – I mean, this could be Commander Whorf reciting his Klingon ancestry, for all I know

•Construction blueprints: it’s bad enough when Ruskin goes off on the proper angles at which the roof is to meet the wall, but at least he has the decency to include illustrations; I have no idea what the Tabernacle or Solomon’s Temple actually looked like, & even if I’ve got a fancy Bible with speculative illustrations, I don’t really need the do-it-yourself instructions, thank you very much

•Specifications for ritual observances: see above on the non-applicability of these instructions (tho it’s nice to know that the priests wore knickers so that they wouldn’t expose themselves as they ascended into the Holy Presence)

Then there are things which are inherently rather interesting, often quite fascinating – but only in moderation; in quantity they become a blur of repetition:

•Psalms – yes, I know, great poetry much of the time, but let’s face it – when you’re spinning 150 of these things out of maybe a half-dozen repeated themes, & recycling the same imagery over and over, it all gets a bit redundantSomewhere in the morass of my office, I have a copy of the Bible which not merely included a lot of snazzy line drawings and helpful maps, but went to the trouble of printing the really dull stuff – the genealogies, the ritual directions, the construction manuals – in a smaller typeface. Now if we can only get New Directions to do that with The Cantos.

•Prophecy – ditto; great poetry, grandly delivered, much of the time: but the message is pretty much the same over and over (with different names slotted into the important slots, I grant): “Come back to Me, O Israel, or have your butt kicked in various ways…”

•Wisdom: proverbs are good in moderate doses (fascinating article on Blake’s proverbs this week in of all places PMLA), but heaven knows they start to blur together when you get an entire book of them; and while Job is one of the basic great reads of Western Lit, as Samuel Johnson said of Paradise Lost, “no-one ever wished it longer.”

•Theological disputation, such as you get in the bulk of the New Testament: now there are those who’ll insist that knowing the details of this stuff is crucial to your eternal salvation etc. – & I’m convinced that one is at a real disadvantage in dealing with most English literature from say 1600 – 1900 without a working acquaintance with at least Romans & Hebrews – but if you don’t have a vested interest in the stuff being argued about, much of it is precisely as fascinating as hearing a poetics argument between Robert Lowell and WD Snodgrass.

Monday, August 14, 2006

Fool's Gold

Blurb-writing 101: Never Write Your Blurb Before You’ve Read the Book You’re Blurbing. Someone should have told Dan Brown this before he blurbed Mario Livio’s The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World’s Most Astonishing Number (Broadway, 2002). Writes Mr B, “you will never again look at a pyramid, pinecone, or Picasso in the same way.”

Phi, former math majors & readers of The Da Vinci Code (Salman Rushdie: “a book so bad it makes bad books look good”; Stephen Fry: “complete loose stool-water,” “arse-gravy of the worst kind”) will know, is the number you get when you divide a line into the “Golden Ratio,” so that the line as a whole bears the same proportion to the longer division as the longer division does to the shorter – on line ABC, AC is to AB as AB is to BC (or AC:AB :: AB:BC). Dividing the longer segment by the shorter, you get the irrational number 1.6180339887… (to no end).

The Fibonacci Series of numbers, in which each successive number is the sum of the preceeding two (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, etc.) (& which Ron Silliman made use of in Ketjak) has the remarkable property, as you divide each number by its precedent, of more and more closely approximating Phi.

Brown made much of the Golden Ratio in The Da Vinci Code, much of it – that Leonardo plotted his Vitruvian man according to the GR, that the Pyramids are based on the GR, etc. – dead wrong, as Livio demonstrates marvelously clearly* in The Golden Ratio, one of those rare books by a scientist that are actually compulsively readable. Indeed, one of the things that makes this book so entertaining is the amount of time it spends debunking various applications of Golden Numerology – all of which Brown seems (from my rather foggy memory of Da Vinci Code) to have swallowed whole. In other words, while there are applications of the Fibonacci series to the arrangement of pinecones, anything relating the Pyramids or Picasso to the golden ratio is just so much hooey – as Brown would have realized if he’d read Livio before praising him.

Reading Livio sent me back to one of my favorite artists, Tom Phillips, whose After Raphael [above] was imprinted on me early by being reproduced on the cover of Brian Eno’s Another Green World. (Eno was a student of Phillips’s at art school.) Unfortunately, like Brown Phillips seems to have swallowed all the balleyhoo about the omnipresence of the golden ratio:

Even the most ill-proportioned visitor to Greece will have it in his bones before he leaves: temple and statue, pillar and pavement, speak the same harmony. Its rediscovery as one of the lost truths of antiquity lay at the heart of the Renaissance. As in the paradox of the poet freed by rhyme, the artist can be liberated by a system of great rigidity. The airy, tender and spacious compositions of Piero reveal, under geometrical analysis, that not an eye or elbow has its place but at the conjunction of lines generated by the overall proportions of the picture.I’m all for being “liberated by a system of great rigidity.” And I suppose the golden section is as good as any other system. But why does everyone have to pretent that the damn thing goes all the way back to the Egyptians, when a little bit of spadework will show otherwise? “Blessed rage for order,” indeed.

I’m just glad LZ never got ahold of the golden ratio; heaven knows he did enough damage with a smattering of second-hand calculus and a fistful of Pythagorean number lore.

*Though not with direct reference to Brown’s book, which didn’t come out until the following year. I suspect Livio’s publisher, which also did the “illustrated” Da Vinci Code, solicited Brown to blurb the paperback of The Golden Ratio.

Among the Democrats

Another weekend over, & that much closer to the beginning of the semester. A headachy day – spent too much time in the sun earlier, at of all things a Palm Beach County Democratic Party picnic. Not, mind you, a fundraiser – just a Party get-together with open invitations encouraging everyone to bring school supplies to donate to local public schools (Jeb Bush being, after all, the “education governor” every bit as much as his brother is a “uniter, not a divider”).

Why’d we go to this thing? Well, Party candidates were gonna be there, & the organizers held out the possibility that the gubernatorial contenders would show. I for one was interested to see what kind of pickings beleaguered Florida Democrats could put up against the loonie who’s the other folks’ front runner right now. But no gubernatorial candidates appeared while we were there, so I was left to conduct a sociological enquiry into the state of Blue politics in South Florida.

One word: old. The average age of the folks there – free food & all – must have been somewhere past retirement age, even with a decent turnout of young people and their children. Seniors mostly white; young people mostly black and Hispanic. Which made it more of a shame that the guy manning the DJ booth was playing what amounted to a golden oldies set. The closest he got to anything with political valence was “Born in the USA” & Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop” (which as you’ll recall got a good deal of airplay during the 1992 Clinton run). The closest he got to music of color was Ray Charles singing “America.” When I suggested to him that the potential voters for a 2020 election might be a little more fired up if he were to play something on the hip-hop, Latino, or even post-James Taylor side of things, he just rolled his eyes and waved a hand at the ranks of grey panthers piled onto the picnic tables under the pavilion: “They’ve already asked me to turn down the volume like 16 times.”

The good folks at the Dems organization had set up two big bounce houses for the kids, & Pippa spent the better part of two hours jumping up & down in the heat, which was oppressive. When she finally came out, we had one of those wonderful “let me tell you how to raise your child” moments: “Did you put sunscreen on that child?” asked one woman; “She looks awfully red & flushed.” As I suppose you would, if you'd been jumping up & down for the better part of 2 hours.

***

Still a bit dazzled from a first reading of Lisa Robertson's fantastic Debbie: An Epic.

Why’d we go to this thing? Well, Party candidates were gonna be there, & the organizers held out the possibility that the gubernatorial contenders would show. I for one was interested to see what kind of pickings beleaguered Florida Democrats could put up against the loonie who’s the other folks’ front runner right now. But no gubernatorial candidates appeared while we were there, so I was left to conduct a sociological enquiry into the state of Blue politics in South Florida.

One word: old. The average age of the folks there – free food & all – must have been somewhere past retirement age, even with a decent turnout of young people and their children. Seniors mostly white; young people mostly black and Hispanic. Which made it more of a shame that the guy manning the DJ booth was playing what amounted to a golden oldies set. The closest he got to anything with political valence was “Born in the USA” & Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop” (which as you’ll recall got a good deal of airplay during the 1992 Clinton run). The closest he got to music of color was Ray Charles singing “America.” When I suggested to him that the potential voters for a 2020 election might be a little more fired up if he were to play something on the hip-hop, Latino, or even post-James Taylor side of things, he just rolled his eyes and waved a hand at the ranks of grey panthers piled onto the picnic tables under the pavilion: “They’ve already asked me to turn down the volume like 16 times.”

The good folks at the Dems organization had set up two big bounce houses for the kids, & Pippa spent the better part of two hours jumping up & down in the heat, which was oppressive. When she finally came out, we had one of those wonderful “let me tell you how to raise your child” moments: “Did you put sunscreen on that child?” asked one woman; “She looks awfully red & flushed.” As I suppose you would, if you'd been jumping up & down for the better part of 2 hours.

***

Still a bit dazzled from a first reading of Lisa Robertson's fantastic Debbie: An Epic.

Saturday, August 12, 2006

I might have been a scholar

if I had ever learned to take notes. A few years ago, I got obsessed with trying to connect Ruskin to the art of Byzantine mosaic (especially the mosaics in Ravenna, which Pound was so crazy about). I had in my head his splendid idea of purchasing selected mosaic tiles from the Vatica fabbrica – which had at least 25,000 different colors available – & having them installed in color-gradient friezes in British art museums for the edification of British artists.

But I couldn't find a bit of documentation for that: not in the dozens of Ruskin volumes kicking around the house, nor in the various biographies and critical studies I owned. So tantalizing – to connect JR to the art which was so crucial to parts of high modernism (EP, Yeats), & which perhaps even provides an analogue for LZ.

I was of course misremembering. The man with the mosaic idea was Darwin's cousin the eugenicist Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911), as quoted in AS Byatt's The Biographer's Tale (2001). In Galton's own words:

In the Fabbrica of mosaics at the Vatican in Rome there are no less that 25000 trays or bins, numbered consecutively, and each filled with cakes of mosaic material, each separate bin being devoted to a different colour…It might well be a subject for the subsequent consideration of the authorities of South Kensington whether they should not select by means of the large amount of skill and science at their disposal say one tenth of the Vatican’s series to create what might be called a South Kensington scale of colours and distribute identical copies of it in mosaic, which would occupy a space according to the above…among the art schools of the United KingdomSimilarly, my last post misremembers what John Latta wrote, or rather rewrites him, drawing upon something else I was reading about the same time. Samuel Delany writes in the essay "Shadow and Ash":

The discursive model through which we perceive the characteristic works of High Modernism – from The Waste Land and Ulysses to The Cantos and Zukofsky's "A" and H.D.'s Helen in Egypt, from David Jones's In Parenthesis and The Anathemata to Charles Olson's Maximus Poems and Robert Duncan's The Structure of Rime and Passages – is that of a foreground work of more or less surface incoherence – narrative, rhetorical, and thematic – behind which stands a huge, and hugely unified, background armamentarium of esoteric historical and esthetic knowledge, which the text connects with through a series of allusions and relations that organize that armamentarium as well as give it its unity.That's nothing at all like what John said; nor is it anything much like what I attributed to him – "High Modernist monumentality sneak[ing] into the post-avant woodpile." But the latter idea, which is something that bears thinking about, seems to me a fusion in my own disordered mind of John's kvetching about "projects" & Chip's large diagnosis of a "post-Modernist" reading experience.

The educated reading such texts request is always a virtual one. Even somebody who is richly familiar with the commentaries and who has studied both sources and text can only hold onto fragments of both background and foreground, and then only for a more or less limited time.

What has happened, of course, is that eventually poets – if not other readers as well – have noted that, with or without access to the background armamentarium, there is nevertheless an experience of reading these texts. [I argued something similar in LZ & the Poetry of Knowledge.] And numerous poets of the last forty years – in not, indeed, the last hundred – have tried to estheticize this affect directly.

A (Stephen) Dedalian danger, my friends, the curse of "Reading two pages apiece of seven books every night, eh?"*

*Ulysses, Chapter 3 ("Proteus"), followed shortly by this striking forecast of LZ: "Books you were going to write with letters for titles. Have you read his F? O yes, but I prefer Q. Yes, but W is wonderful. O Yes, W."

Thursday, August 10, 2006

My Latest Big Project

Been (re)reading a bit of the Good Book: the first stretch of Genesis (Creation thru Abram), Amos, Judith (you go, girl!). And what I'm told is a very Evil book, Philip Pullman's The Amber Spyglass. And feeling, in the face of greybeards with Big Projects and young people with boundless energy, very middle-aged, fat, & lazy, like a cat in the Florida sun. Can't even write what I've already promised to write, much less plot out enough volumes of poetry for the rest of my life.

John's got it right about those life-plans:

John's got it right about those life-plans:

I love how the lingo of twentieth-century big science, all a-doozy amongst the earnestines, comes to invade the poetry circles. Everybody’s got they “project.” They “next” project. Manhattan Project, “lifework” project, same dish. (Wait for the next plausible monicker to out, the avant-garde taking its military nod seriously in the grim “age of hits”: the “operation.” Not as in “chance operation,” no—“Operation Big Chance,” or “Operation Fueled by Flowers,” or “Operation Wrong’d Narcissist.” “I’m in the midst of “Operation Blank Cartridge,” the going’s rough, though I should end up with a chapbook.”)Methinks he's revised the post, & I liked the earlier one, about how High Modernist monumentality sneaks into the post-avant woodpile: Bruce Andrews rewriting Dante, Ron S. trying to outdo Ez, WCW, Olson, & LZ all at once. Gosh I admire the energy: now who's our Michael Drayton, & who's our Charles Montagu Doughty? (Worthies both, but did they need to write so much?)

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

Old Wine / New Bindings

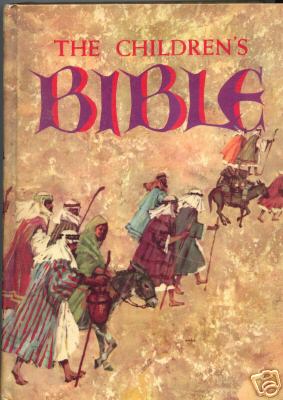

The last time I visited my mother's house in Tennessee, I spent a number of hours hunting thru bookshelves, boxes, and drawers for one of the great books of my childhood, a vividly illustrated "Children's Bible." I couldn't find the book, but I paged thru a copy in a used bookstore yesterday, & recognized every single one of the paintings I laid eyes on: the blinded Samson pushing apart the pillars of the Philistine temple; the prophet Daniel being hauled out before, & refusing to worship, Nebuchadnezzar's golden image; the rebel Absalom with his Robert Plant-like locks tangled in a tree branch, awaiting the death blow.

The last time I visited my mother's house in Tennessee, I spent a number of hours hunting thru bookshelves, boxes, and drawers for one of the great books of my childhood, a vividly illustrated "Children's Bible." I couldn't find the book, but I paged thru a copy in a used bookstore yesterday, & recognized every single one of the paintings I laid eyes on: the blinded Samson pushing apart the pillars of the Philistine temple; the prophet Daniel being hauled out before, & refusing to worship, Nebuchadnezzar's golden image; the rebel Absalom with his Robert Plant-like locks tangled in a tree branch, awaiting the death blow.I do have in my study, however, a slightly later acquisition: a lavishly annotated & appendicized King James Version published by the John A. Dickson company of Chicago in the sort of leather binding that must be laid flat (on a coffee table, presumably) rather than shelved, presented to me by my parents in January 1975. I never thought I'd ever buy another "presentation" Bible – after all, I've entered all the family genealogical data into this one, & there are a number of other KJVs kicking around the house & the office (the Oxford World's Classics, which I've been teaching out of, a little portable thing in black binding, and an odd "original spelling" edition the Thomas Nelson people put out some years back), not to mention the various others – the New English, an NIV, Everett Fox's Five Books of Moses, various volumes of the Anchor Bible...

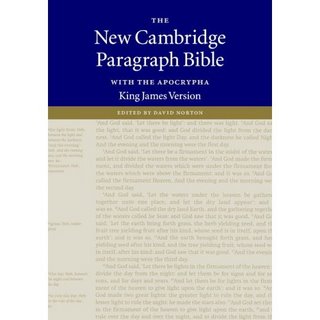

But today Amazon delivered up the presentation copy of David Norton's New Cambridge Paragraph Bible (CUP, 2005). Did I want another huge book that can't really be shelved? Not really, but the regular CUP hardcover seems to be already out of print, & at least this comes in a cardboard slipcover that stands it upright. What's most revelatory, however, is Norton's approach to editing this volume. He's not a theologian or Biblical scholar per se, but a textual critic, & his goal is not to somehow get the KJV closer to the Hebrew & Greek (& Aramaic) texts of the Bible, but to get this KJV closer to what the original translators of 1611 intended.

But today Amazon delivered up the presentation copy of David Norton's New Cambridge Paragraph Bible (CUP, 2005). Did I want another huge book that can't really be shelved? Not really, but the regular CUP hardcover seems to be already out of print, & at least this comes in a cardboard slipcover that stands it upright. What's most revelatory, however, is Norton's approach to editing this volume. He's not a theologian or Biblical scholar per se, but a textual critic, & his goal is not to somehow get the KJV closer to the Hebrew & Greek (& Aramaic) texts of the Bible, but to get this KJV closer to what the original translators of 1611 intended.Most folks who use the KJV aren't aware that the vast majority of King James Bibles out there reproduce the text, not of the 1611 Authorized Version, but of a 1769 revision thereof. In short, the editors & publishers of the AV saw fit to tinker with the text – changing punctuation, wording, spelling – for about 150 years before they decided to settle down and stick with a single version. So the KJV one encounters today is essentially a mid 18th-century version of the 1611 text, with mid 18-th c. spellings & punctuation.

Norton has gone back to the first edition & beyond that to the translators' notes & manuscripts. For the most part, he's returned to 1611 punctuation, which he feels is actually closer to contemporary usage than the 1769 punctuation. At a number of textual cruxes, he's found the KJV translators more convincing than their revisors: when Paul, in 1 Timothy 2.9, urges "that women adorn themselves in modest apparel, with shamefacedness and sobriety" (this is the received AV), Norton points out that the 1611 translators wrote in "shamefastness and sobriety." To be "shamefaced" is to be ashamed; so might "shamefast," but it's more compellingly read as "holding fast to modesty."*

At the same time, this is a modernized text, in the same way that almost all texts of Shakespeare we read are modernized: spelling, especially, has been brought up to date, & some of the more vexing verb tenses have been sorted out (you have no idea how much agony the verb "bear" – as in childbearing, KJV past tense "bare" – routinely causes my students). Weird archaisms have been replaced with clearer cognates: the Philistines in 1 Samuel 5 don't have "emerods" any more, but more prosaic "haemorrhoids." Norton has inserted quotation marks for speeches, & heaven knows how many troubles that'll clear up.

But what's most compelling about this KJV are not the tinkering with text & orthography but the formatting. As its title indicates, it's a "paragraph" Bible, which means that instead of the maddening World's Classics format (each verse a separate paragraph, double columns), this Bible has broad single text columns, divided into real live paragraphs (with verse divisions indicated by teeny superscript numbers). It's this particular innovation (not really new, since the first Cambridge Paragraph Bible came out in 1873 or so) that makes this the most readable KJV on the block.

Of course, I'm not assigning this monster to my Bible as Lit students this fall, & I'm not recommending anyone out there buy this presentation volume, either (for heaven's sake, it doesn't even have a family register!); turns out that the David Norton Cambridge text will be the basis for the forthcoming Penguin Classics Bible, due out in three weeks or so.

*No connection to recent discussion of mammary exposure in 17th-c. portraiture.

fashion update

No nipples this time, but this from Richard B. Schwartz's Daily Life in Johnson's London:

In a period when the bizarre was often commonplace, one of the more striking fashions was the post-Revolution, 1790s technique for imitating the aristocrats who had gone to the guillotine. Englishwomen wore thin crimson ribbons around their necks and had their hair tousled, in a style termed la victime coiffeur.

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Ex-Prospective Juror

Most of the day burnt up in jury duty, where I learnt that voir dire (OF "to say the truth," the process by which jury pools are interrogated & weeded out) can be pronounced "vaw dar" by a judge of the circuit court around here, & where I was dismissed after several excruciatingly dull hours (without even having to use the words "ambulance chaser" in connection with the civil trial I was trying out for). Rewarded myself by visiting a couple of book- & music-stores. The haul:

***

Good news from Connecticut. Be careful whom you kiss, or who kisses you...

***

Goodness, an actual conversation in the comments box! I hasten to say, Henry, that at no point did I want to cast aspersions on your review of John's Breeze – it's just that John's response to the review clicked in my mind with Jessica's comment on wanting her work to be read on its own terms – it started me thinking what a pigeon-holing mind my own is, how I'm always looking for a conceptual folder to file the new things in. Or how I'm always trying to locate things on some sort of conceptual/historical map, so that I can figure out how someone got "there" from "here."

When my maps were getting drawn, there were a certain number of things that got filled in first, while the rest was still "Here Be Dragons," & pace Norman – tho I will defer to your advanced age – they weren't necessarily the "best"; often, the best came later ("I have had to learn the simplest things..." – my motto, courtesy Charley O.). But the things that I encountered first still have the sort of warm spot in memory that one's shitty hometown does, or the lousy diner one ate at every week during college – if only because there weren't any diners in one's s. hometown, & it was the best one in one's rural collegetown.

Is that HW's version of the Mallarmé? I resent his losing the force of the active verb – "j'ai lu tous les livres."

The 2-CD Skeleton Crew set from RER (Fred Frith, Tom Cora, Zeena Parkins)All in all, a very "downtown" stack. On DVD:

Marc Ribot Y Los Cubanos Postizos, Muy Divertido!

John Zorn/Wayne Horvitz/Elliott Sharop/Bobby Previte, Downtown Lullaby

The collector's edition of Monty Python & the Holy GrailIn paper: a nice Penguin Grundrisse, the recent Vintage reissue of Samuel Delany's Fall of the Towers, & the one Lemony Snickett novel that we hadn't yet read.

The film of Peter Brooks's production of Marat/Sade

***

Good news from Connecticut. Be careful whom you kiss, or who kisses you...

***

Goodness, an actual conversation in the comments box! I hasten to say, Henry, that at no point did I want to cast aspersions on your review of John's Breeze – it's just that John's response to the review clicked in my mind with Jessica's comment on wanting her work to be read on its own terms – it started me thinking what a pigeon-holing mind my own is, how I'm always looking for a conceptual folder to file the new things in. Or how I'm always trying to locate things on some sort of conceptual/historical map, so that I can figure out how someone got "there" from "here."

When my maps were getting drawn, there were a certain number of things that got filled in first, while the rest was still "Here Be Dragons," & pace Norman – tho I will defer to your advanced age – they weren't necessarily the "best"; often, the best came later ("I have had to learn the simplest things..." – my motto, courtesy Charley O.). But the things that I encountered first still have the sort of warm spot in memory that one's shitty hometown does, or the lousy diner one ate at every week during college – if only because there weren't any diners in one's s. hometown, & it was the best one in one's rural collegetown.

Is that HW's version of the Mallarmé? I resent his losing the force of the active verb – "j'ai lu tous les livres."

Monday, August 07, 2006

Oh yeah, I meant to cross-reference that last comment to Jessica's post a couple weeks ago, which went something like: Don't tell me who my work's like, don't tell me that it reminds you of this or that or the other, at least make the effort to describe the bits that you like or don't like about it on their own terms.

Poetry is Hard To Talk About

So Henry Gould reviews John Latta's Breeze, a really splendid book of poems that displays the same range of omnivorous interests & wild gaiety of diction as JL's various blogs, & then there's a little blog back 'n' forthing:

JL: Thank'ee much, v. v. honored, perhaps it ain't all Wallace Stevens (dunno if I've read him all), but I did hang out a lot with Archie Ammons in Ithaca, & wonder if some of that foul-mouthed transcendentalism rubbed off?

HG: Thank'ee for the thank'ee, back to the drawing board.

(Love that "Old Peanut-head" – Temple of Zeus, every morning, swapping dirty jokes with Mike Abrams...)

But that's the fallback, isn't it? You read a new book of poems, you compare it with what you've read before – & if you're writing about it, you dress up those comparisons with the finery of "influence" & "artistic genealogy." It's not always lazy – any critical procedure, any approach can be lazy, a substitute for thinking – it's not lazy when HG does it with JL. It tells us important things: this reader wants to know exactly how Hart Crane was important to early Olson, how DH Lawrence "influenced" Creeley, what Bishop got from Marianne Moore, usw. (& man was I happy when John Matthias located Anarchy in the same tea party with Geoffrey Hill & Susan Howe, "if one can imagine either one of these poets also taking an interest in Johnny Rotten and the Sex Pistols.")

It's an effect of age, of having read things, innnit? My Theory is that each of us has a half-dozen books or poets that serve as baseline comparisons for almost everything that comes after in our reading: & it's not because they're the best or the first at doing whatever they do, supreme exemplars etc., but because they're the first we encountered doing that thing. They become central reference points that one works backwards & forwards from. So that I for one read the Paradise Lost passages of "A"-14 (1964) and Tom Phillips's A Humument (1970) in the light of Ron Johnson's RADI OS – only because I read RADI OS first, & i had never encountered anything like it before. All "literary" ballads stand for me in some relation to John Crowe Ransom's "Captain Carpenter" (encountered aet. 17 or 18).

One reason I'm so enjoying Martha Ronk's Eyetrouble (Georgia, 1998) & In a Landscape of Having to Repeat (Omnidawn, 2004) – I don't know what to compare 'em to, & have given up trying.

"Willing suspension of disbelief" – give me a willing – willed – temporary – suspension of textual memory.

JL: Thank'ee much, v. v. honored, perhaps it ain't all Wallace Stevens (dunno if I've read him all), but I did hang out a lot with Archie Ammons in Ithaca, & wonder if some of that foul-mouthed transcendentalism rubbed off?

HG: Thank'ee for the thank'ee, back to the drawing board.

(Love that "Old Peanut-head" – Temple of Zeus, every morning, swapping dirty jokes with Mike Abrams...)

But that's the fallback, isn't it? You read a new book of poems, you compare it with what you've read before – & if you're writing about it, you dress up those comparisons with the finery of "influence" & "artistic genealogy." It's not always lazy – any critical procedure, any approach can be lazy, a substitute for thinking – it's not lazy when HG does it with JL. It tells us important things: this reader wants to know exactly how Hart Crane was important to early Olson, how DH Lawrence "influenced" Creeley, what Bishop got from Marianne Moore, usw. (& man was I happy when John Matthias located Anarchy in the same tea party with Geoffrey Hill & Susan Howe, "if one can imagine either one of these poets also taking an interest in Johnny Rotten and the Sex Pistols.")

It's an effect of age, of having read things, innnit? My Theory is that each of us has a half-dozen books or poets that serve as baseline comparisons for almost everything that comes after in our reading: & it's not because they're the best or the first at doing whatever they do, supreme exemplars etc., but because they're the first we encountered doing that thing. They become central reference points that one works backwards & forwards from. So that I for one read the Paradise Lost passages of "A"-14 (1964) and Tom Phillips's A Humument (1970) in the light of Ron Johnson's RADI OS – only because I read RADI OS first, & i had never encountered anything like it before. All "literary" ballads stand for me in some relation to John Crowe Ransom's "Captain Carpenter" (encountered aet. 17 or 18).

One reason I'm so enjoying Martha Ronk's Eyetrouble (Georgia, 1998) & In a Landscape of Having to Repeat (Omnidawn, 2004) – I don't know what to compare 'em to, & have given up trying.

"Willing suspension of disbelief" – give me a willing – willed – temporary – suspension of textual memory.

Friday, August 04, 2006

Louis Zukofsky: Selected Poems (ed. Charles Bernstein)

I make no excuses for only having recently gotten around to reading thru Charles’s selection of LZ for the Library of America’s “American Poets Project” series. Afer all, I have a nodding acquaintance with much of the work included here. What’s new, of course, is Charles’s selection & arrangement. Last year (or was it year before last?) Ron Silliman spent several long blog posts agonizing over what ought to go into a short selected LZ, & I did the same; both of us, of course, were in consultation with Charles – “in on the secret,” as it were. But it’s Charles’s baby, ultimately, & I’m very happy to report that he’s done just a fine job of it.

The problem with selecting LZ for a wide audience – perhaps even an audience that doesn’t turn to poetry on a regular basis, judging by the promotional materials & subscription offers the LOA keeps sending me – is that the bits of LZ most highly valued by those who’ve been reading him for decades are apt to pose really formidable challenges to the casual reader: “A”-9, 80 Flowers, the impacted collages of “A”-22 & -23. At the same time, there’s a good deal of LZ that pays off the reader for whom immediate apprehension is a necessary prequel to pleasure: large swatches of “A”-12, many of the short poems (in particular the valentines). (This is the LZ which most closely resembles Williams on the one hand & parts of Creeley on the other, the LZ which proved so attractive to Cid Corman.) And then there’s the work that hovers between the two extremely of dense hermeticism & graceful lucidity – the majority of the writing, I’d hazard.

Charles, to his credit, devotes the bulk of his selection to this “mid-range” work and to the more obdurate & difficult – at the same time sprinkling the volume with enough well-chosen examples of “easy” LZ to keep a less-committed readership awake. Emblematic are 2 of the 3 long “pivotal” texts Charles includes (the 1st, inevitably, is a long sample from “Poem beginning ‘The,’” in some ways the Transformer* of LZ’s early career – a flashy and quite impressive early work that unfortunately sometimes obscures what comes after): “4 Other Countries” & “A”-23. I think the selection would have been a failure had Charles not included “A”-22 or -23 in its entirety (indeed, I’d love to see the 2 movements reissued in a single volume), because they’re the culmination of “late” LZ, & a fountainhead for a whole range of interesting subsequent writing.

But it’s Charles’s inclusion of the whole of “4 Other Countries,” the longest of LZ’s poems outside of “A”, a poem that could be loosely described as a travelogue tracking the Z family’s 1957 tour of Europe – the 4 countries of the title are England, France, Italy, & Switzerland – that it’s worth drawing attention to. Ron was not particularly enthusiastic about this piece taking up almost 40 pages of the selection. I can’t lay my hand on his specific post, but I seem to recall him regretting how it made LZ seem more Williamsesque than was accurate.

10 years ago, I might have agreed; now, with Charles’s selection in hand, I’m inclined to see including “4 Other Countries” as a pretty canny decision. The poem, that is, is an exemplary transition work in LZ’s corpus, the poem in which the plain-spoken, legible statement drawn over short lines – Williams’s trademark – begins to become the mosaic, the collage of impressions & quotations. And it’s here that the shortlines most exemplarily drive the syntax of the poem thruout, in ways that WCW only accomplished at the top of his form.

If there’s an “argument” to Charles’s selection – and ofcourse everyone who edits such a book is making an argument – then it’s a diachronic one, that one way of reading LZ is to note how his poetry evolves over the course of his career from a straightforward, if “crabbed,” idiom (“Poem beginning ‘The,’” the passages of “A”-12) to reach its fruition in the tangible word-stuff of “A”-23 & 80 Flowers. “4 Other Countries” is indispensible as a snapshot of LZ’s work in the midst of that evolution. The missing link, that is, between “To my wash-stand” & “Zinnia.”

The problem with selecting LZ for a wide audience – perhaps even an audience that doesn’t turn to poetry on a regular basis, judging by the promotional materials & subscription offers the LOA keeps sending me – is that the bits of LZ most highly valued by those who’ve been reading him for decades are apt to pose really formidable challenges to the casual reader: “A”-9, 80 Flowers, the impacted collages of “A”-22 & -23. At the same time, there’s a good deal of LZ that pays off the reader for whom immediate apprehension is a necessary prequel to pleasure: large swatches of “A”-12, many of the short poems (in particular the valentines). (This is the LZ which most closely resembles Williams on the one hand & parts of Creeley on the other, the LZ which proved so attractive to Cid Corman.) And then there’s the work that hovers between the two extremely of dense hermeticism & graceful lucidity – the majority of the writing, I’d hazard.

Charles, to his credit, devotes the bulk of his selection to this “mid-range” work and to the more obdurate & difficult – at the same time sprinkling the volume with enough well-chosen examples of “easy” LZ to keep a less-committed readership awake. Emblematic are 2 of the 3 long “pivotal” texts Charles includes (the 1st, inevitably, is a long sample from “Poem beginning ‘The,’” in some ways the Transformer* of LZ’s early career – a flashy and quite impressive early work that unfortunately sometimes obscures what comes after): “4 Other Countries” & “A”-23. I think the selection would have been a failure had Charles not included “A”-22 or -23 in its entirety (indeed, I’d love to see the 2 movements reissued in a single volume), because they’re the culmination of “late” LZ, & a fountainhead for a whole range of interesting subsequent writing.

But it’s Charles’s inclusion of the whole of “4 Other Countries,” the longest of LZ’s poems outside of “A”, a poem that could be loosely described as a travelogue tracking the Z family’s 1957 tour of Europe – the 4 countries of the title are England, France, Italy, & Switzerland – that it’s worth drawing attention to. Ron was not particularly enthusiastic about this piece taking up almost 40 pages of the selection. I can’t lay my hand on his specific post, but I seem to recall him regretting how it made LZ seem more Williamsesque than was accurate.

10 years ago, I might have agreed; now, with Charles’s selection in hand, I’m inclined to see including “4 Other Countries” as a pretty canny decision. The poem, that is, is an exemplary transition work in LZ’s corpus, the poem in which the plain-spoken, legible statement drawn over short lines – Williams’s trademark – begins to become the mosaic, the collage of impressions & quotations. And it’s here that the shortlines most exemplarily drive the syntax of the poem thruout, in ways that WCW only accomplished at the top of his form.

If there’s an “argument” to Charles’s selection – and ofcourse everyone who edits such a book is making an argument – then it’s a diachronic one, that one way of reading LZ is to note how his poetry evolves over the course of his career from a straightforward, if “crabbed,” idiom (“Poem beginning ‘The,’” the passages of “A”-12) to reach its fruition in the tangible word-stuff of “A”-23 & 80 Flowers. “4 Other Countries” is indispensible as a snapshot of LZ’s work in the midst of that evolution. The missing link, that is, between “To my wash-stand” & “Zinnia.”

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

Lines from Bruce Andrews’s Ex Why Zee:

John Evelyn’s description of the aftermath of the Great Fire of London, 1666:

***

Oliver Cromwell (for Steven Moore)

He read of children tossed

at a pike’s end, of cannons

with “God Is Love” scribed round

their barrels. He read of a snake

with garnet eyes, of golden

ringlets curling round the hemp

of a hangman’s noose.

He read of green fields

and mines, of foundries

and factory floors. Pleasures

and game diversions. The tree

which bursts into pink blossoms

of enthusiasm. The trees huddle

suspiciously in the wind, rustle

in green whispers. A village mashed

and shattered under the sun, not one

stone left upon another. Bombers

and fighter jets darkening the sun,

the shop clerk whose weekend sends

him – in militiaman’s uniform –

to take stock – with a bayonet– of a

tentful of refugees. Great men,

whose brows line with the effort

of shaping destiny. Who read old books,

and find their faces there.

(in progress)

Body = society, we think of punishment as refinement, and yet: nothing is natural, body just another android fun machine. Genres are fucked; disturb the creature – we need our own spanking rhetorical body.***

I used to be a radical formalist, but now / I’m a derivative spiritual humanist / with better funding opportunities.

John Evelyn’s description of the aftermath of the Great Fire of London, 1666:

The fountaines dried up & ruind, whilst the very waters remained boiling; the Voragos of subterranean Cellars Wells & Dungeons, formerly Warehouses, still burning in stench & dark clowds of smoke like hell, so as in five or six miles traversing about, I did not see one loade of timber unconsum’d, nor many stones but what were calcind white as snow, so as the people who now walked about the ruines, appeard like men in some dismal desart, or rather in some greate Citty, lay’d wast by an impetuous & cruel Enemy, to which was added the stench that came from some poore Creaturs bodys, beds, & other combustible goods.(Vorago, “an abyss, gulf, or chasm.”)

***

Oliver Cromwell (for Steven Moore)

He read of children tossed

at a pike’s end, of cannons

with “God Is Love” scribed round

their barrels. He read of a snake

with garnet eyes, of golden

ringlets curling round the hemp

of a hangman’s noose.

He read of green fields

and mines, of foundries

and factory floors. Pleasures

and game diversions. The tree

which bursts into pink blossoms

of enthusiasm. The trees huddle

suspiciously in the wind, rustle

in green whispers. A village mashed

and shattered under the sun, not one

stone left upon another. Bombers

and fighter jets darkening the sun,

the shop clerk whose weekend sends

him – in militiaman’s uniform –

to take stock – with a bayonet– of a

tentful of refugees. Great men,

whose brows line with the effort

of shaping destiny. Who read old books,

and find their faces there.

(in progress)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)